John Brittas, Author (Rajya Sabha member from Kerala, belonging to the CPM)

The esteemed American economist and humanist John Kenneth Galbraith once characterized India as a functional anarchy. Galbraith, who also held the position of ambassador to India, expressed this sentiment in appreciation of a civilization where diversity is regarded as a strength rather than a liability.

One might speculate on Galbraith’s perspective had he encountered modern India, where diversity is often perceived as a cultural threat and political dissent is interpreted as conspiracy. The current climate in India, characterized by the potential dominance of a single leader, party, election, language, and faith, would likely have disconcerted him.

Those in power assert that they possess exclusive knowledge of what is best for the nation, promoting a narrative of homogenization. They identify the southern states as the primary obstacle to achieving this objective.

Fault Line 1: Delimitation, a potential political upheaval

A significant concern is the proposed delimitation process. Article 82 of the Constitution mandates the reallocation of Lok Sabha seats following each Census to reflect updated population data. However, this process has been on hold since 1976, with the freeze later extended by the Vajpayee administration to ensure equitable representation.

With the current government postponing the 2021 Census and planning for delimitation ahead of the 2029 elections, the implications for southern India could be dire.

Population estimates as of March 2025 suggest that the total number of Lok Sabha seats could rise to approximately 790 on a pro-rata basis. While Kerala is expected to retain its 20 seats, Uttar Pradesh is projected to increase its representation from 80 to 133 seats. As a result, the southern states’ share of Lok Sabha seats would decrease from the current 24 percent of 543 seats to merely 19 percent, while the Hindi belt’s representation would grow from 32 percent to 38 percent.

Moreover, the process of reapportionment would affect the seats reserved for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, shifting the dynamics of reservation in favor of the northern regions. This intentional redistribution of power could exacerbate regional inequalities and threaten the federal structure of India. Should the southern states lose their capacity to form coalitions to oppose constitutional amendments, their influence in national policymaking would be significantly weakened.

Fault Line 2: Language imposition and the struggle for identity

Language continues to be a contentious issue in the relations between the North and South. Since the education policies of 1968 and 1986, the central government has advocated for a three-language formula, which includes Hindi, English, and a regional language in educational institutions. However, this approach has primarily favored Hindi, leading to a decline in linguistic diversity. In northern India, regional languages such as Bhojpuri and Maithili have experienced a downturn due to the predominance of Hindi.

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 purports to provide flexibility in language selection; however, in reality, there is a strong push for Hindi, while support for other languages remains insufficient. Statistics indicate that over 90 percent of residents in the Hindi-speaking regions are monolingual, in contrast to the multilingual capabilities observed in southern states. Additionally, states like Tamil Nadu and Kerala, which demonstrate higher levels of English proficiency, consistently achieve better rankings on the Human Development Index (HDI) and Gross Enrolment Ratios (GER), while states where Hindi is predominant tend to fall behind.

The initial draft of the NEP in 2019 proposed making Hindi mandatory in non-Hindi states, prompting the government to engage in damage control following widespread protests. The South perceives this as part of a broader initiative to culturally homogenize India, relegating regional languages to a lesser status.

Fault Line 3: Education policies — centralized authority and political pressure

The Centre has utilized funding as a mechanism to compel states to align with its policies. The centrally sponsored Samagra Shiksha scheme, which finances educational initiatives, has been selectively withheld from states such as Tamil Nadu and Kerala for their failure to implement the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 or the PM SHRI project. Tamil Nadu has had ₹2,152 crore blocked, affecting 40 lakh students and 32,000 staff members, while Kerala has been denied ₹849.2 crore.

The transfer of education from the State List to the Concurrent List through the 42nd Amendment has enabled the Centre to impose education policies without adequately addressing the concerns of the states. While Gujarat, under Narendra Modi’s leadership, successfully eliminated the governor’s involvement in university matters, states governed by the Opposition have encountered obstacles in enacting similar reforms. The new UGC regulations further undermine state autonomy by granting governors extensive authority over the appointment of vice-chancellors in state universities, despite states covering 76 percent of their educational expenditures.

Fault Line 4: Financial discrimination, characterized by the unequal allocation of resources

Financial devolution has been a longstanding issue, with southern states contributing disproportionately to the national tax revenue while receiving significantly less in return. The South perceives this financial disparity as an unjust penalty for its superior governance and economic discipline. The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Finance Commissions recommended devolving 42 percent and 41 percent of net tax revenue to states, yet the actual share received has decreased to 30 percent in 2023-24. When considering three aspects—share from Central Taxes, grants mandated by the Finance Commission, and funds allocated through centrally sponsored schemes—the South feels overlooked and penalized for its commendable performance.

In contrast, Uttar Pradesh, which contributes far less in taxes, has received more central funding than all the southern states combined.

Despite the increased funding, states such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh continue to face challenges related to high fertility rates, inadequate education, and fragile healthcare systems, prompting concerns regarding the effective use of these funds.

Fault Line 5: One Nation, One Election – A Threat to Federalism?

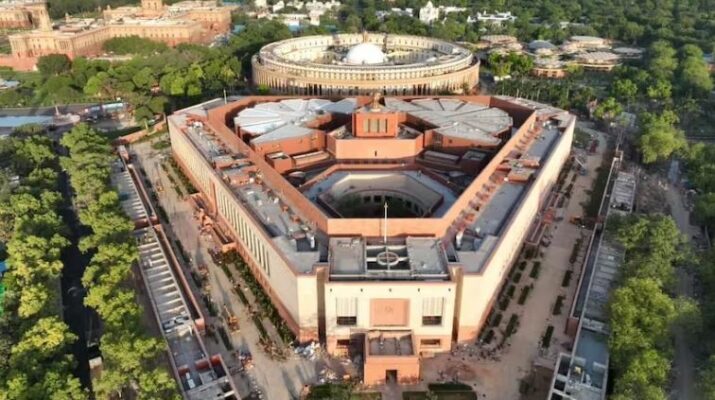

The initiative for One Nation, One Election (ONOE) represents a further move towards centralization. The Indian Constitution allocates distinct powers to both the Union and the states as outlined in Schedule VII. The Supreme Court’s decision in the Kesavananda Bharati case reaffirmed that federalism is a fundamental aspect of the Constitution’s structure.

Implementing ONOE would necessitate synchronizing state assembly terms with those of the Lok Sabha, which could lead to either premature dissolutions or arbitrary extensions. This approach undermines the constitutional assurance of five-year legislative terms and subjects state governments to central authority. The proposal introduces a new Article 82A, which empowers the President, based on the Election Commission’s advice, to postpone or cancel state elections. For southern states, ONOE poses a significant threat to their autonomy.

The broader context: A move towards centralized governance?

Controversial legislation, including the Goods and Services Tax (GST), the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, and new criminal laws, has been enacted without substantial consultation with the states. The persistent drive for a “one nation” approach—whether through One Nation, One Election; One Nation, One Tax; One Nation, One Civil Code; or One Nation, One Language—focuses not on efficiency but on imposing a singular identity. This vision favors the Hindi-Hindu core while marginalizing southern India and other non-Hindi regions.

Rising discontent in the South

The frustration in the South is not simply a response to recent developments but rather the result of decades of policy choices. The essential question remains: What truly defines India? A genuine federal democracy recognizes and values its diversity instead of enforcing uniformity.